A Tale of Four Cities

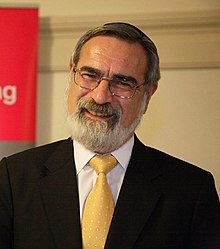

Rabbi Jonathan Sacks 1948-2020

The following Torah reflection was written by Rabbi Jonathan Sacks who served as the Chief Rabbi of the United Hebrew Congregations of the Commonwealth from 1991-2013. Enjoy!

Between the Flood and the call to Abraham, between the universal covenant with Noah and the particular covenant with one people, comes the strange, suggestive story of Babel:

The whole world spoke the same language, the same words. And as the people migrated from the east they found a valley in the land of Shinar and settled there. They said to each other, “Come, let us make bricks, let us bake them thoroughly.” They used bricks for stone and tar for mortar. And they said, “Come, let us build ourselves a city and a tower that reaches the heavens, and make a name for ourselves. Otherwise we will be scattered across the face of the earth.”

Gen. 11:1-4

What I want to explore here is not simply the story of Babel considered in itself, but the larger theme. For what we have here is the second act in a four act drama that is unmistakably one of the connecting threads of Bereishit, the Book of Beginnings. It is a sustained polemic against the city and all that went with it in the ancient world. The city – it seems to say – is not where we find God.

The first act begins with the first two human children. Cain and Abel both bring offerings to God. God accepts Abel’s, not Cain’s. Cain in anger murders Abel. God confronts him with his guilt: “Your brother’s blood cries out to me from the ground.” Cain’s punishment was to be a “restless wanderer on the earth.” Cain then “went out from the Lord’s Presence and lived in the land of Nod, east of Eden.” We then read:

Cain knew his wife, and she conceived and gave birth to Enoch. He [Cain] built a city, naming it Enoch after his son.

Gen. 4:17

The first city was founded by the first murderer, the first fratricide. The city was born in blood.

There is an obvious parallel in the story of the founding of Rome by Romulus who killed his brother Remus, but there the parallel ends. The Rome story – of children fathered by one of the gods, left to die by their uncle, and brought up by wolves – is a typical founding myth, a legend told to explain the origins of a particular city, usually involving a hero, bloodshed, and the overturning of an established order. The story of Cain is not as founding myth because the Bible is not interested in Cain’s city, nor does it valorise acts of violence. It is the opposite of a founding myth. It is a critique of cities as such. The most important fact about the first city, according to the Bible, is that it was built in defiance of God’s will. Cain was sentenced to a life of wandering, but instead he built a town.

The third act, more dramatic because more detailed, is Sodom, the largest or most prominent of the cities of the plain in the Jordan valley. It is there that Lot, Abraham’s nephew, makes his home. The first time we are introduced to it, in Genesis 13, is when there is a quarrel between Abraham’s herdsmen and those of Lot. Abraham suggests that they separate. Lot sees the affluence of the Jordan plain.

Lot raised his eyes and saw that the whole plain of the Jordan up to Tzoar was well watered. It was like the garden of the Lord, like the land of Egypt.

Gen. 13:10

So Lot decides to settle there. Immediately we are told that the people of Sodom are “evil, great sinners against the Lord” (Gen. 13:13). Given the choice between affluence and virtue, Lot unwisely chooses affluence.

Five chapters later comes the great scene in which God announces his plan to destroy the city, and Abraham challenges him. Perhaps there are fifty innocent people there, perhaps just ten. How can God destroy the whole city?

“Shall the Judge of all the earth not do justice?”

Gen. 18:25

God then agrees that if there are ten innocent people found, He will not destroy the city. In the next chapter, we see two of the three angels that had visited Abraham, arrive at Lot’s house in Sodom. Shortly thereafter, a terrible scene plays itself out:

They had not yet gone to bed when all the townsmen, the men of Sodom – young and old, all the people from every quarter – surrounded the house. They called to Lot, “Where are the men who came to you tonight? Bring them out to us so that we may know them.”

Gen. 19:4-5

It turns out that there are no innocent men. Three times – “all the townsmen,” “young and old,” “all the people from every quarter” – the text emphasises that without exception, every man was a would-be perpetrator of the crime.

A cumulative picture is emerging. The people of Sodom do not like strangers. They do not see them as protected by law – nor even by the conventions of hospitality. There is a clear suggestion of sexual depravity and potential violence. There is also the idea of a crowd, a mob. People in a crowd can commit crimes they would not dream of doing on their own. The sheer population density of cities is a moral hazard in and of itself. Crowds drag down more often than they lift up. Hence Abraham’s decision to live apart. He wages war on behalf of Sodom (Gen. 14) and prays for its inhabitants, but he will not live there. Not by accident were the patriarchs and matriarchs not city dwellers.

The fourth scene is, of course, Egypt, where Joseph is brought as a slave and serves in Potiphar’s house. There, Potiphar’s wife attempts to seduce him, and failing, accuses him of a crime he did not commit, for which he is sent to prison. The descriptions of Egypt in Genesis, unlike those in Exodus, do not speak of violence but, as the Joseph story makes pointedly clear, there is sexual license and injustice.

It is in this context that we should understand the story of Babel. It is rooted in a real history, an actual time and place. Mesopotamia, the cradle of civilisation, was known for its city states, one of which was Ur, from which Abraham and his family came, and the greatest of which was indeed Babylon. The Torah accurately describes the technological breakthrough that allowed the cities to be built: bricks hardened by being heated in a kiln.

Likewise the idea of a tower that “reaches to heaven” describes an actual phenomenon, the ziqqurat or sacred tower that dominated the skyline of the cities of the lower Tigris-Euphrates valley. The ziqqurat was an artificial holy mountain, where the king interceded with the gods. The one at Babylon to which our story refers was one of the greatest, comprising seven stories, over three hundred feet high, and described in many non-Israelite ancient texts as “reaching” or “rivalling” the heavens.

Unlike the other three city stories, the builders of Babel commit no obvious sin. In this instance the Torah is much more subtle. Recall what the builders said:

“Come, let us build ourselves a city and a tower that reaches the heavens, and make a name for ourselves. Otherwise we will be scattered across the face of the earth.”

Gen. 11:4

There are three elements here that the Torah sees as misguided. One is “that we make a name for ourselves.” Names are something we are given. We do not make them for ourselves. There is a suggestion here that in the great city cultures of ancient Mesopotamia, people were actually worshipping a symbolic embodiment of themselves. Emil Durkheim, one of the founders of sociology, took the same view. The function of religion, he believed, is to hold the group together, and the objects of worship are collective representations of the group. That is what the Torah sees as a form of idolatry.

The second mistake lay in wanting to make “a tower that reaches to the heavens.” One of the basic themes of the creation narrative in Bereishit 1 is the separation of realms. There is a sacred order. There is heaven and there is earth and the two must be kept distinct:

“The heavens are the heavens of the Lord, but the earth He has given to the children of men.”

Ps. 115:16

The Torah gives its own etymology for the word Babel, which literally meant “the gate of God.” The Torah relates it to the Hebrew root b-l-l, meaning “to confuse.” In the story, this refers to the confusion of languages that happens as a result of the hubris of the builders. But b-l-l also means “to mix, intermingle,” and this is what the Babylonians are deemed guilty of: mixing heaven and earth, that should always be kept separate. B-l-l is the opposite of b-d-l, the key verb of Bereishit 1, meaning “to distinguish, separate, keep distinct and apart.”

The third mistake was the builders’ desire not to be “scattered over the face of the whole earth.” In this they were attempting to frustrate God’s command to Adam and later to Noah to “Be fruitful and multiply and fill the earth.” (Gen. 1:28; Gen. 9:1). This seems to be a generalised opposition to cities as such. There is no need, the Torah seems to be saying, for you to concentrate in urban environments. The patriarchs were shepherds. They moved from place to place. They lived in tents. They spent much of their time alone, far from the noise of the city, where they could be in communion with God.

So we have in Bereishit a tale of four cities: Enoch, Babel, Sodom, and the city of Egypt. This is not a minor theme but a major one. What the Torah is telling us, implicitly, is how and why Abrahamic monotheism was born.

Hunter/gatherer societies were relatively egalitarian. It was only with the birth of agriculture and the division of labour, of trade and trading centres and economic surplus and marked inequalities of wealth, concentrated in cities with their distinctive hierarchies of power, that a whole cluster of phenomena began to appear – not just the benefits of civilisation but the downside also.

This is how polytheism was born, as the heavenly justification of hierarchy on earth. It is how rulers came to be seen as semi-divine – another instance of b-l-l, the blurring of boundaries. It is where what mattered were wealth and power, where human beings were considered in the mass rather than as individuals. It is where whole groups were enslaved to build monumental architecture. Babel, in this respect, is the forerunner of the Egypt of the Pharaohs that we will encounter many chapters and centuries later.

The city is, in short, a dehumanising environment and potentially a place where people worship symbolic representations of themselves.

Tanach is not opposed to cities as such. Their anti-type is Jerusalem, home of the Divine Presence. But that, at this stage of history, lies long in the future.

Perhaps the most relevant distinction for us today is the one made by the sociologist Ferdinand Tonnies, Gemeinschaft (community) and Gesellschaft (society). Community is marked by face-to-face relationships in which people know, and accept responsibility for, one another. Society, in Tonnies’ analysis, is an impersonal environment where people come together for individual gain, but remain essentially strangers to one another.

In a sense, the Torah project is to sustain Gemeinschaft – strong face-to-face communities – even within cities. For it is only when we relate to one another as persons, as individuals bound together in shared covenant, that we avoid the sins of the city, which are today what they always were: sexual license, the worship of the false gods of wealth and power, the treatment of people as commodities, and the idea that some people are worth more than others.

That is Babel, then and now, and the result is confusion and the fracturing of the human family.